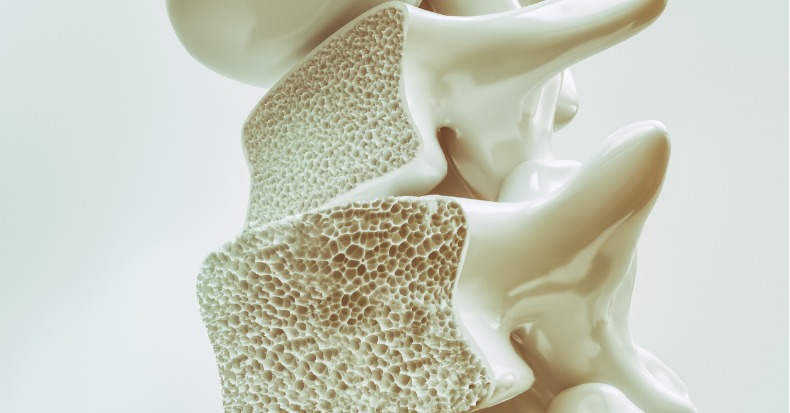

So, what does bone density have to do with low back pain? The relationship between bone density and back pain is quite intimate. In fact, when the degree of bone density declines to the point of fracture, back pain becomes very real. The classic condition and cause of spinal pain associated with the loss of bone density is a compression fracture.

Compression fractures occur when the strength of the bone decreases to a point where minor trauma—and sometimes no trauma whatsoever—can result in fracture. Compression fractures most often affect the vertebral body (front of the spine) in the upper lumbar or lower thoracic spine but the pain associated with these types of fractures frequently radiates into the low back and pelvic region. In the elderly osteoporotic spine, these types of fractures usually do not result in spinal cord injury or nerve damage but this is quite the opposite when compression fractures occur in younger, normal bone density individuals. This is because when the bone is dense (or normal), the vertebral body basically explodes or bursts, shifting some of the bony fragments back into the spinal canal where the spinal cord is located. When bone density decreases, there is no bursting of fragments—only collapse, resulting in pain but no neurological damage. Besides pain, another problem with compression fractures is that the once upright or vertical spine is now bent and angles forward shifting the patient’s weight to the front. This shift places yet more pressure on both the fractured vertebra and the surrounding vertebra which increases the risk of fracture to the surrounding adjacent vertebra. Therefore, multiple compression fractures are not uncommon when brittle bones occur from osteoporosis.

So, who is more at risk for osteoporosis? The usual predictors include age (older than 65), gender (female), race (Asian or Caucasian), low body weight, and a previous fracture. Others include smoking, previous use of corticosteroids, a family history of fracture, excessive alcohol use, and rheumatoid arthritis. Additionally, vitamin D deficiency, hyperthyroidism, and celiac disease (gluten intolerance), as well as poor balance (repeated falls), muscle weakness, and a DEXA (dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry) T-score of -1.1 to -2.4 (osteopenia) or -2.5 or greater (osteoporosis) are also important predictors of brittle bone disease or osteoporosis. To best determine your risk using these factors, go to FRAX (www.sheffield.ac.uk/frax) developed by the World Health Organization (WHO) to determine your ten-year fracture probability (do not just use of the T-score on the DEXA scan).

From a treatment standpoint, it depends on the age of the patient, the degree of osteoporosis, and whether fracture has already occurred. In the younger osteopenic person (that is, no fractures have occurred, yet but bone density is low), non-medication approaches such as weight bearing exercise, no smoking, calcium / vitamin D supplementation, and minimize the other risk factors described above may be the proper choice. For others already with fracture, medication (bisphosphonates such as Actonel, Boniva, and Fosamax) may be appropriate. Further, injecting a cement into the bone (called kyphoplasty) may be appropriate for some.